Mayor's column: Breaking down the rates rise

Mayor Tim Cadogan - Opinion

23 March 2024, 4:30 PM

Central Otago Mayor Tim Cadogan. PHOTO: File

Central Otago Mayor Tim Cadogan. PHOTO: FileSo how the hell did we get to a place where council is looking at an average residential rates rise of just under 25%?

This will be quite a long column so please bear with.

Before giving the reasons to the above question though, I need to say that no elected members are happy about this situation, or don’t realise that it is going to cause some people some significant challenges. If we had a reasonable way out of it, we would take it, believe me.

And there’s another thing before we get into the meat of the why, and that is that CODC is not alone in this situation. I am sure you will have read that councils across the country are facing record rates risings this coming financial year.

So, there’s a number of things that have led us here. They are all interconnected, but easier to understand if I break them down.

The first is rising costs to do the things we do. A big piece of that is down to inflation, which you of course will know is high, but is also dropping.

A common and understandable question though is why inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is around 6% and our rates increase is in the mid 20’s. That’s because inflation is only part of our problem, and because the inflation councils deal with is not the CPI inflation that is the usually quoted figure.

Anyone who has built or renovated a house in the last few years will know that build inflation is the bloated cousin of CPI inflation and that the cost of building stuff has gone up at a far higher rate than CPI.

And, the problem is, councils build stuff. LGNZ had economics firm Infometrics run some data to demonstrate the problem. This showed that since the last Long Term Plan (LTP) three years ago, bridges are 38% more expensive to build, sewerage systems are 30% more expensive and roads and water supply systems are around 27% more expensive.

Outside of the build inflation, we have taken a number of hits in other cost centres. For instance, our overall energy cost (electricity and fuel) is set to increase by around $500,000 (or around one rates percentage point) in the next financial year. Alongside that, our insurance cost will go up by around $400,000. That’s a staggering figure and is in part linked to Gabrielle and the Auckland floods.

Then there is the cost of doing the things that the Government tells us we have to do. I’ll give just one example of many to illustrate that. New regulations have come in from central government (CG) that require councils to monitor water more closely and that monitoring is costing something in the vicinity of $30,000 a month, and as I say, that’s just one example.

Which leads me nicely to the second thing that has got us in this mess, and that is unfunded mandates from government, of which there are a seemingly endless supply.

An unfunded mandate is where Central Government in Wellington says to local government “thou shalt do ABC and XYZ” but provides no money for local government (LG) to do it. The Three Waters space provides some massive examples of these. One is drinking water, where CG has decreed (in 2021) that all council (and almost all private) drinking water supplies will have multi-barrier protection.

This was as a result of the Havelock North water disaster and comes at a cost of tens of millions of dollars for CODC alone, with no support from CG.

Add to that the current direction of travel from CG that wastewater plants will not get consent over the next couple of decades as they fall due if they are discharging treated (even highly treated) wastewater to other water bodies and the costs go through the roof.

Spit ball a number for what it will cost to get Alexandra and Clyde’s treated wastewater to land-based disposal and you will be talking over $100m, and then start thinking of the other five plants in Central that will need transferred and the problem becomes, in my view, insurmountable.

Which takes me to the structural problem at the root of most of this mess and that is the share of the nation’s tax-take that councils get in New Zealand compared to CG.

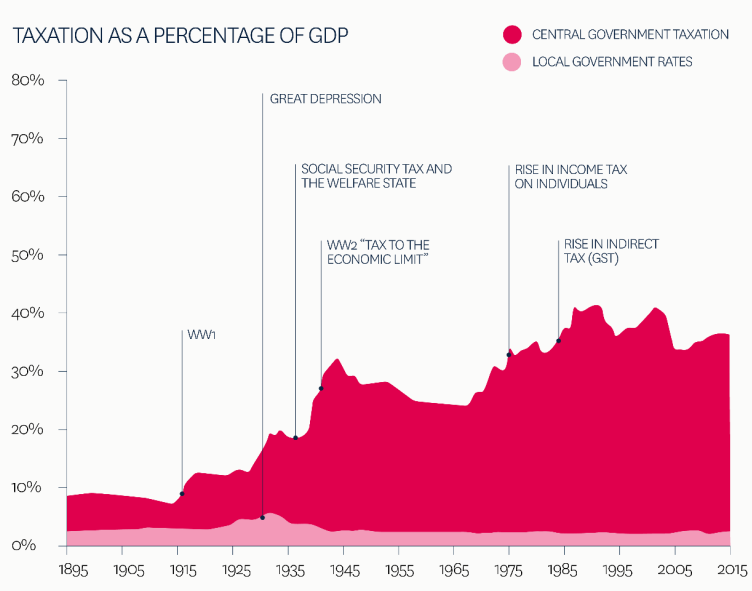

New Zealand is an absolute outlier in this regard. Below is a graph that shows that the percentage of the combined CG/LG tax take as a portion of the nation’s GDP stretching from 1895 to 2015. You will see that LG’s share has stayed at around 2% of GDP since the late 19th century while CG’s has grown from around 8% to around 35 after peaking at close to 40%.

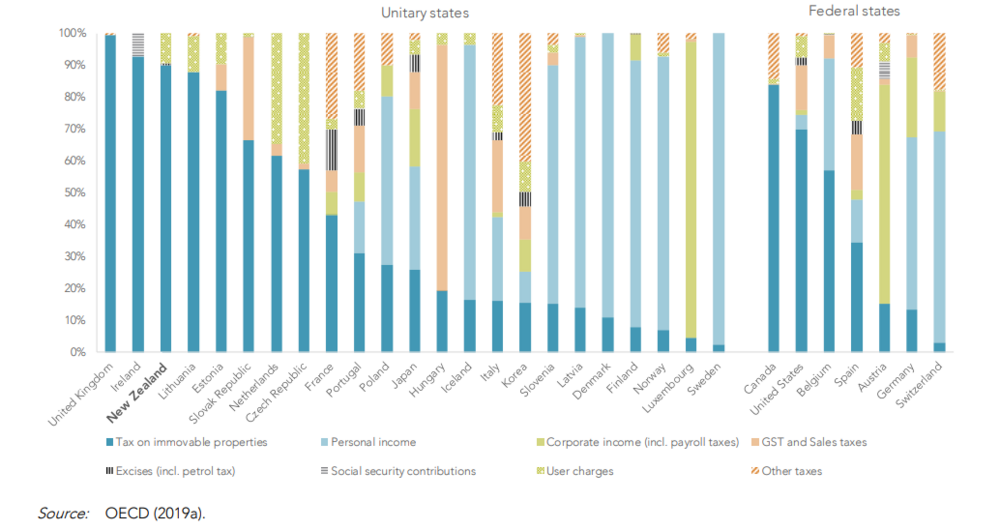

The above graph alone shows the system councils operate under at present is fundamentally broken. But how does this compare to the rest of the world? The OECD graph below is from 2019, but little will have changed to these structures since then. It shows New Zealand as third highest for reliance on tax on immovable properties (ie rates) compared to countries we like to compare ourselves to for local government income.

The graph is hard to read, especially if you are on a phone, but the bits of the lines that aren’t dark blue, predominantly on the left side, are forms of income that CG allows LG in other countries to use instead of taking it themselves, such as income and sales tax.

The complexities of the problems are too great to go into much further here as the column is a monster as it is. Suffice to say, in my opinion the system of local government in New Zealand is fundamentally broken and the rates rises we are seeing across the country is a glaring symptom of that.

So, what can we do about these problems?

The big one of a system no longer fit for purpose is being championed by LGNZ, the parent organisation for councils to which CODC belongs. But more important I am sure to you is what do we do about the rates rise that is currently proposed, and the answer is unfortunately we do not have many places to move.

We don’t have assets readily available to sell to meet some of the costs we face and we can’t, or won’t, take risks such as slashing our insurance cover to lower that staggering $400,000 increase in premiums.

A tactic that is tempting and employed by quite a number of councils, but we have chosen not to, is cutting depreciation.

This gets a wee bit complex so again, bear with me.

Depreciation is all about inter-generational funding, meaning users of long-term infrastructure pay for the replacement infrastructure as it is “consumed”.

So, let’s take a bridge built in 1975 with an anticipated life-span of 50 years. If the cost of that bridge was paid for in 1975, then the people of 1975 have paid for all of it.

Those of us who have driven over the bridge since then have been getting a free ride, right? If it gets replaced next year and the people of 2025 pay cash for it, then the people of 1975 and 2025 are getting screwed over and the people of the other years from 1975 through until 2075 (presuming the new bridge has a 50-year lifespan) are laughing. Not fair right?

If we were to build the new bridge next year, we would debt fund it, meaning as the debt is paid back, the people over the years paying the debt are paying their share as they use, or consume, the bridge.

That is one way to ensure inter-generational equity, and depreciation is another. This is where people essentially pay in advance, knowing something is going to need replaced, or significantly repaired, in the future.

This is an overly simplified way of describing a complex accounting practice, but the essence of it is that we need to balance the cost of long-term infrastructure over the people using it over its lifetime.

Depreciation makes up 29% of the increase to the costs to council in the coming financial year and it is very tempting to cut funding for that across the board as a means of lowering the huge increase.

But, and here’s the moral dilemma, if we do that, we are saying that we will consume the assets today without paying our share and leave the cost of replacing them to the people of tomorrow.

Councils across the country, in some instances including ourselves, have employed this practice in the past, but putting things off until tomorrow to hide the real costs from today is not something this council is willing to do apart from in a small number of cases where we can see it makes sense.

This has been a really long column and I feel like I have only skirted over the top of the complexities. If you have got this far, thank you. If you want to talk more, drop me an email at [email protected] and I’ll give you a ring.